This post is also available in:

Français

Français

Antonin Plarier, ATER (History), Sciences Po Grenoble

From the very first moment of the Algerian independence war, the prefect of Batna was concerned about the presence of “bandits” in the National Liberation Army (ALN). As a result of this, the prefect deduced the need to regroup the Algerian people because these “bandits” had social and logistic support. In the prefect’s view, regroupment camps would have to eradicate this support.

This apparent contradiction in the superimposition of a criminal phenomenon on a political phenomenon raised questions and led to this PhD thesis. This field of enquiry was fueled by reading the work of Eric Hobsbawm, a historian who became a pioneer as well as an essential and much discussed reference within this branch of history. In Bandits (1969), he proposed analyzing banditry as a phenomenon that occurs as a result of changes in rural societies. This interpretation was interesting as it positioned banditry within the context of colonization. Eric Hobsbawm added that these “social bandits” set themselves up as much as they were set up as figures of peasant resistance.

This insight offered, half a century after its publication, a means of constantly challenging our understanding of banditry within the context of colonialization.

Hence, one of the questions raised was whether this banditry could be interpreted as an anticolonialist phenomenon.

This question was obviously not the only one raised when putting together the thesis project supervised by Sylvie Thénault, and the sources consulted during the first years of research reinforced the need to broaden our approach to banditry. At the end of this period of research, the central question simply turns out to be: Who are these bandits? In other words, how were connections constantly established between the bandits and their rural world?

How is the history of banditry to be interpreted?

This issue necessitated an investigation on several fronts. Judiciary or police material, which was rather limited, did not provide enough evidence to identify the phenomenon. This one should be restored to its social environment.

To do so, the land and forest records of the National Overseas Archives (Aix-en-Provence) and the Algerian National Archives required consultation.

This enabled snapshots to be gleaned of the bandits or their milieu at precise moments in their history. The collection of these fragments provided clues about the bandits and shed a furtive but illuminating light on certain episodes in this period or figures within the bandit community. It also provided a framework for the environment in which bandits emerged, a framework that was essential for interpreting / framing banditry as a “total social fact” (Marcel Mauss, « Essai sur le don » in Sociologie et Anthropologie, PUF, 2001 [1921]).

And besides, to which social reality does banditry refer? The term banditry has negative connotations and is used in a multitude of literary media which above all convey moral condemnation.

Nevertheless, the authors of the period, from gendarmes to eloquent journalists, not only express indignation or admiration when they discuss banditry. They also reveal facts, acts, relationships, conflicts, sometimes even emotions. It then becomes possible to take an interest in those who, having committed a crime, are pursued by the administration and refuse to submit to their laws. In this refusal lies the very definition of banditry, as these fugitives end up appropriating this label.

Constant connections with rural life

The bandits experience and share a daily rural existence. The antagonism they express is first and foremost that of this daily existence. The bandit story is one of peasants struggling with dispossession. One of the elements of this thesis is an analysis of this dispossession phenomenon, which is not so much about land dispossession since this phenomenon has been written about by other historians. The main focus is on peasant customs and their reconsideration by the forestry administration. This complex process unfolds unevenly among the Algerian forest territories. If the forest code adopted in 1827 applies theoretically from the time of the conquest in 1830, its implementation on a practical level takes effect over a longer period as the colonial authority exerts greater control.

The forestry administration is progressively expanding, prioritizing its establishment in the cork oak forests, which are highly attractive economically. Until the beginning of the 20th century, some forest areas are not covered by the administration. The demarcation of these spaces requires time and resources and does not occur without provoking opposition and conflicts. Maintaining grazing rights, continuing to use fire as an agricultural technique for soil fertilization, preserving the right to collect or cut wood for domestic or artisanal purposes are all casus belli. These conflicts are sporadic in the long run but they animate and punctuate the entire colonial period. They also facilitate the accommodation of rangers who exist in relative isolation due to the nature of their work.

What meanings should we apply to banditry?

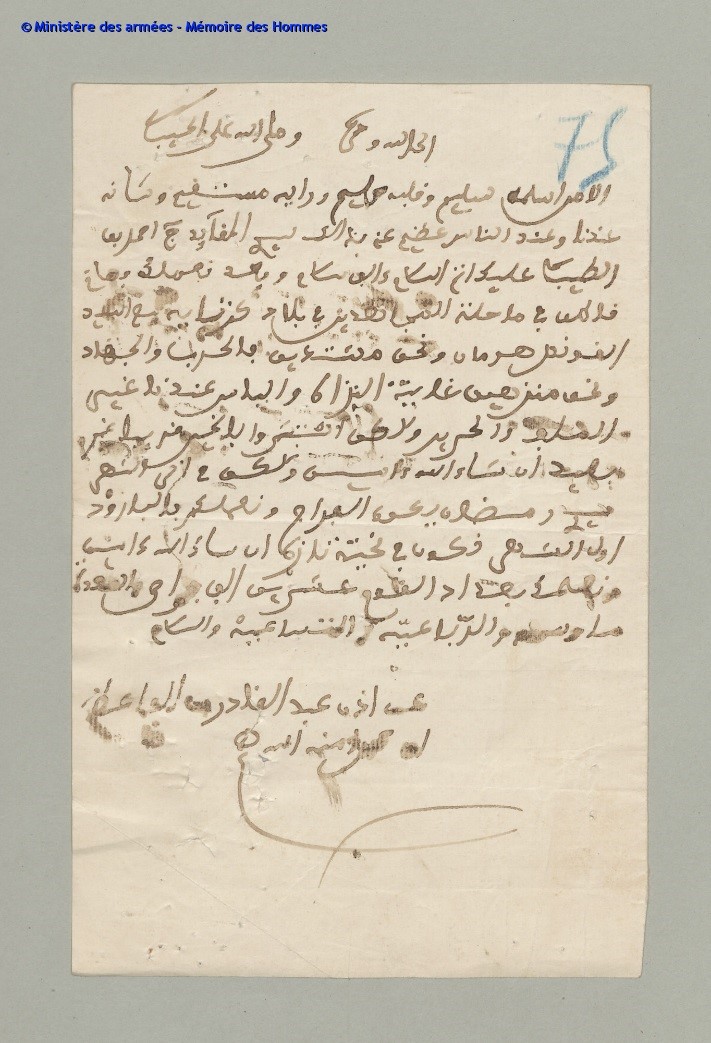

In this context, what does banditry mean, i.e. what meaning can the actors attribute to their actions? The obvious difficulty in addressing this question lies not only in the fact that these bandits have written very little, but of this only an infinitesimal quantity has been saved.

It was therefore necessary to scrutinize what little was written whilst simultaneously shining a light on the diction used at the time.

From this research, it is obvious that the protagonists, former peasants for the most part, are not spared any of the various kinds of dispossession. Therefore, the repetition of acts forbidden by the administration (forest grazing, agricultural fire, wood cutting or simply robberies) is a form of opposition to the authorities whose colonial character accentuates the violence. Banditry is therefore part of a continuum that begins with rural illegalism and progresses to insurrection.

Colonialism is not the only cause of banditry. The preferred scientific approach to understanding this phenomenon is from more of a social history perspective than a colonial history angle stricto sensu, which would make colonialism the only engine of social relations in a parallel situation. I have therefore demonstrated the recurrence of a direct or indirect involvement of rural Europeans in banditry, whether in the indirect form of support or in the more direct form of an involvement in banditry. Indeed, the corpus of bandits studied includes some Italian and Spanish bandits, which provides testimony of the administration’s perception of the European immigrant population. This European involvement makes our reading of banditry more complex, a phenomenon which is in fact an integral part of rural life and which only expresses conflicts in a paroxysmal way.

Tracking and repression of banditry

The resistance aspect of banditry ultimately exists due to the administration deciding to repress this phenomenon. This decision to repress ultimately makes sense of banditry. The coercive panoply put in place includes a variety of administrative, military and judicial measures that blend together in what is primarily an intelligence battle before becoming a physical confrontation between two camps. This physical confrontation is, however, far from systematic. In this intelligence battle, the actors possess multiple assets.

Contrary to widespread misconception, the administration does encounter difficulties understanding what is happening among the Algerian population yet, it is not ignorant of local realities. By the same token, bandits also have resources to fight or dodge colonial authority.

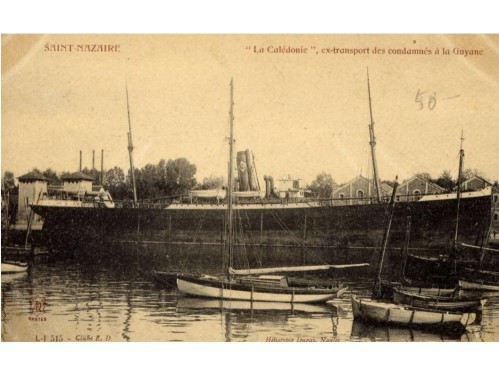

Throughout these chapters, a micro-historian approach has been favored. The trajectories of bandits transported to penal colonies in Guyana or New Caledonia, informed in particular by individual convict records, allowed me to restore individual paths through the empire, positioning this work in imperial history.

Therefore a feature of this thesis is not to favour an historical approach to the detriment of any other but to frame it in social, environmental and imperial history enabling the definition of an object in different facets and phases of its existence.

Banditry and insurrection: the advent of the First World War

During the First World War, banditry is defined by its specific refusal to join in the war effort. This refusal feeds it and gives it life and unprecedented vigor. Interspersed, these two phenomenon provoke the concern of the colonial administration who sense danger.

This danger is realised thanks to the insurrection of 1916 which arises in the Belezma. A bandit named Mohammed ben Nouï plays a leading role in this revolt and thus makes real the colonial anxieties that interpret banditry as a pre-insurrectional phenomenon. A great deal of anger is unleashed during this dramatic episode.

Within the group that led the initial assault, during which were assassinated a sub-prefect and a commune chief (administrateur de commune), some individuals became bandits following their convictions for various forest crimes while others joined the group as a result of draft-evading or deserting. This anger mingles into a mille-feuille of protest. In this context, banditry is simply an avatar of its environment. This transformation that takes place as war proceeds makes banditry a banner which brings to light the social and political demands of the rural population of Algeria.