This post is also available in:

Français

Français

Pierre Bréchon, Frédéric Gonthier and Sandrine Astor, Grenoble Alpes University, CNRS, Sciences Po Grenoble, Pacte

The public debate on French values is more than ever riddled with alarmist interpretations. The 2018 European Values Survey really deals with some of these preconceived ideas.

The rise of individualism, the decline of the republican and secular matrix, the weight of immigration … all these factors, combined with sluggish growth and rising inequality, are allegedly leading to a polarized society, and breaking down national cohesion. The French part of the European Values Survey provides perspective on this hypothesis.

People’s morals are steadily becoming more liberal

The EVS has been tracking significant long term change since 1981 throughout the European continent, and questions representative of national samples of people on values varying from morality, sociability, or politics to religion and the economy.

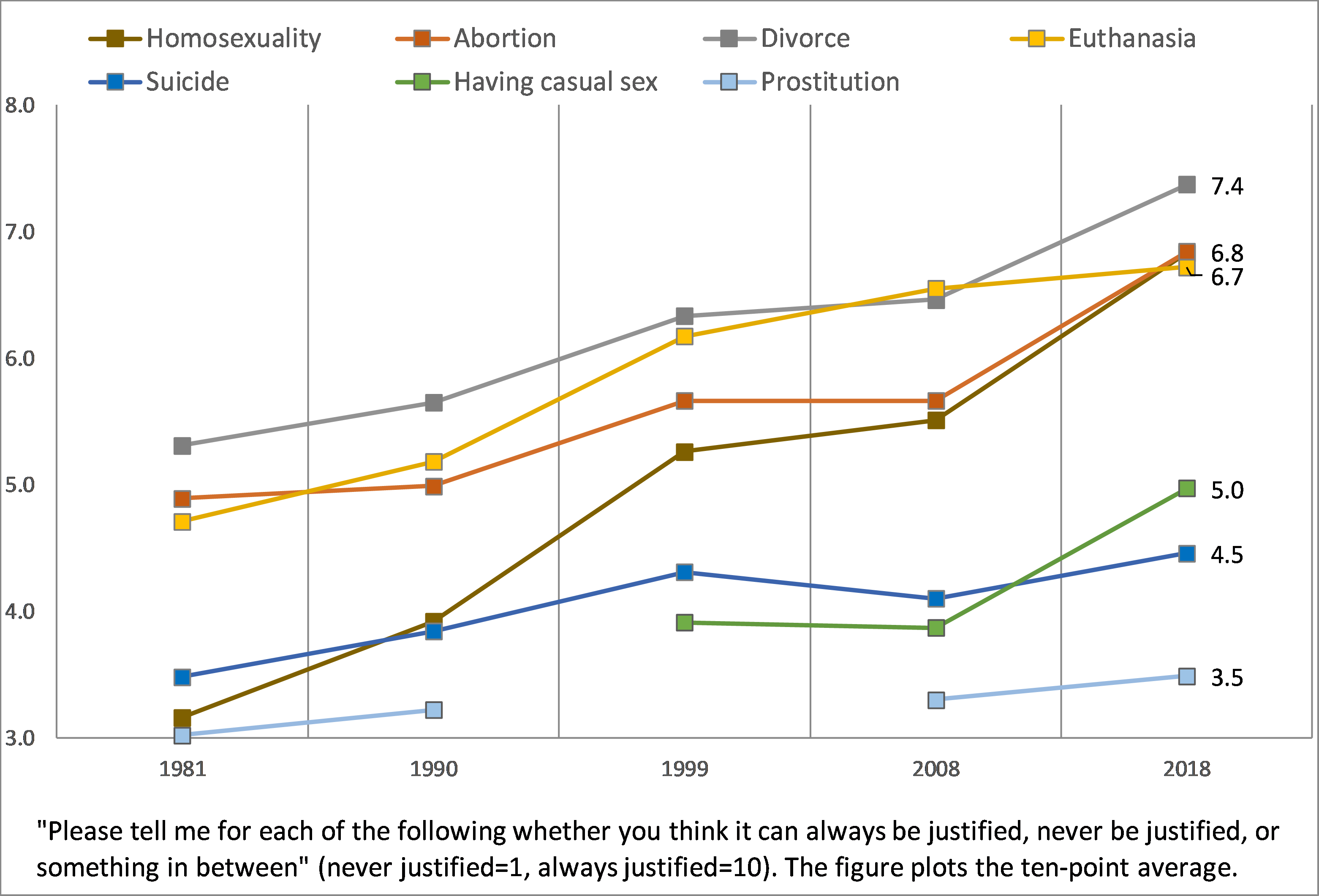

The survey measures French people’s opinions on family relationships, people’s relationship to their body or their sexuality (see the first figure). Social liberal behavior is better accepted today than forty years ago. The acceptance of suicide and of casual sex has grown significantly. But it is views on homosexuality, euthanasia, abortion and divorce that have really moved on. Yet, although the French tend to have increasingly liberal moral attitudes, certain behavior, such as prostitution, is still not very tolerated.

Acceptance also depends on the period. Social liberalism increased sharply between 1981 and 1999, then capped in the early 2000s, and has taken off again since 2008. During the 1990s, there was still some resistance from the public to, for example, the PACS civil union, which took a long time to become legal. Yet, the many debates on same-sex marriage, the right to euthanasia or artificial insemination have accelerated the acceptance of liberal mores over the last ten years.

But context does not explain everything. The liberalization of mores since the 1980s has largely been the result of the changing generations, with young people being much more open than their elders. It is interesting to note that the young people of the 1980s are now older but are just as tolerant as the young people of the beginning of the twenty-first century. We are thus witnessing a phenomenon of convergence, with all generations showing high levels of tolerance as far as moral matters are concerned. Only seniors who grew up before 1945 are a little less open to freedom of choice.

Altruism resists recession

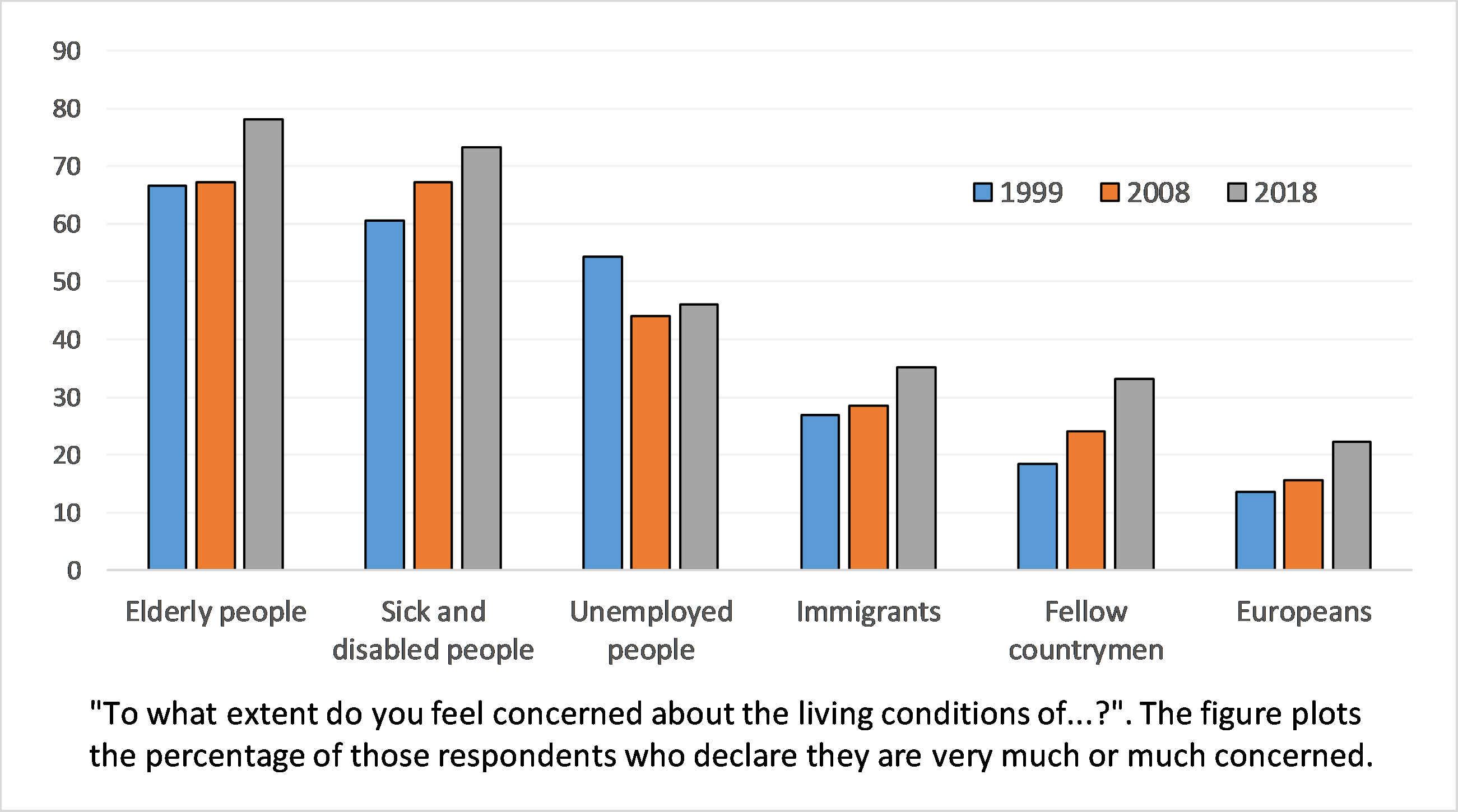

Solidarity with others follows a very similar pattern. In contrast to pessimistic theses, a fairly large majority of French people say they are concerned about other social groups’ living conditions (see the second figure). People are naturally more altruistic towards the elderly, sick or disabled than towards the unemployed and immigrants, but they care more about unemployed people and immigrants than ordinary fellow citizens or Europeans. French people are therefore clearly very sensitive to the new forms of dependency linked to old age, disability or long-term unemployment.

While we might have expected a decline following the Great Recession, we are currently seeing a surge of altruism, especially towards the elderly and immigrants which is probably the result of activism by political parties and the associative sector in favor of migrants and refugees.

Here again, structural factors are key. It is among the younger generations that caring about other people has progressed the most. Interestingly, people born in the 1960s were for a long time the least altruistic; which might explain certain problems with social cohesion. Yet, today, the gap between generations has narrowed and the younger generations are just as altruistic as the others. This trend is all the more remarkable as young people are among the most exposed in periods of recession.

Well-anchored values of social democracy

Many analysts feared that the economic recession would lead to erosion of democratic values and attachment to the welfare state. The French are clearly very dissatisfied with the functioning of the political system. The average is of 4.7 out of 10 on a scale ranging from 1 (“not satisfied at all with how the political system is functioning in France these days”) and 10 (“completely satisfied”). And many think that France is not governed democratically, with a 6.4 average on a similar ten-point scale (1 meaning “not at all democracy” and 10 “completely democratic”).

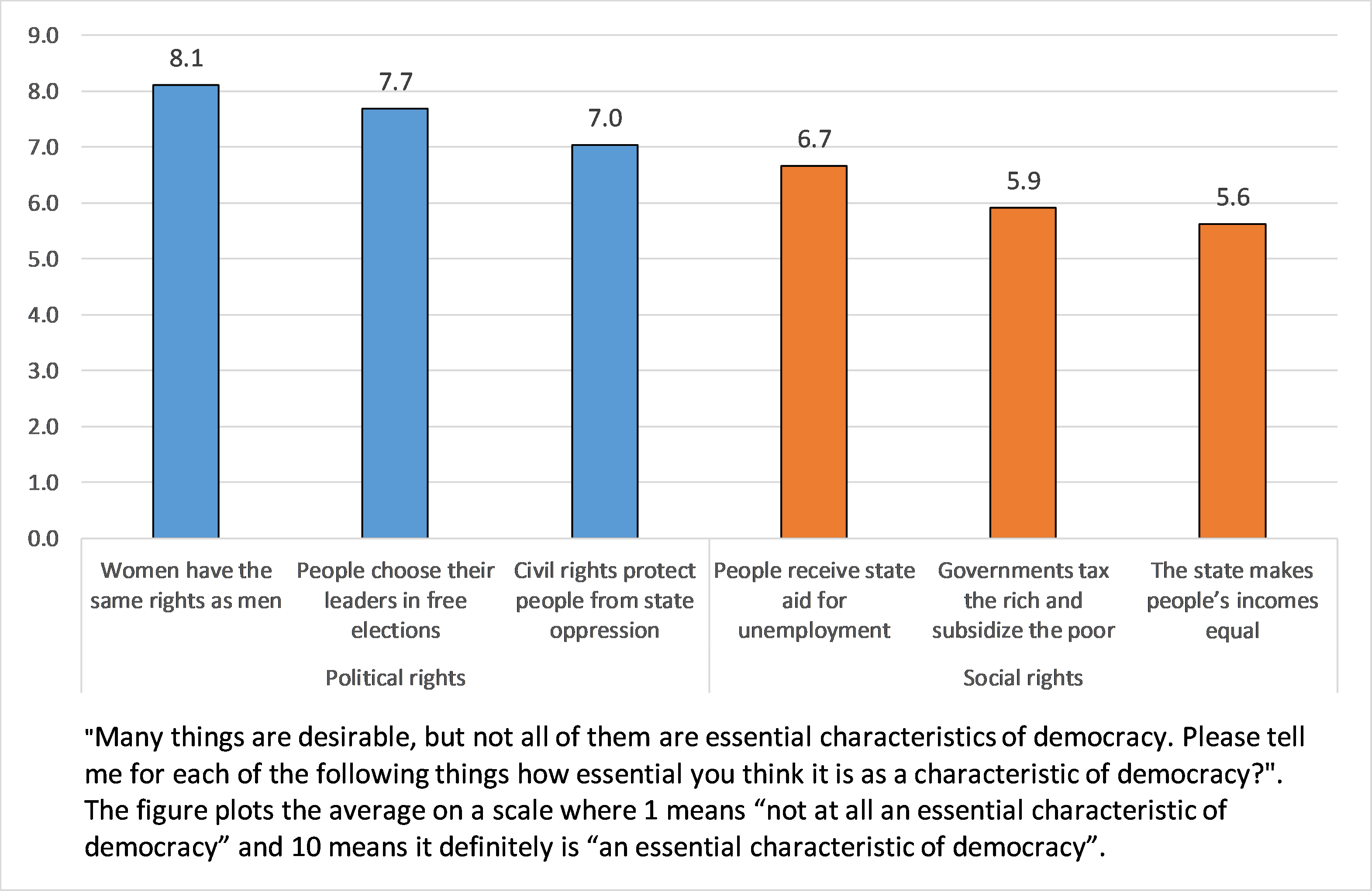

It would be wrong, however, to infer that they reject the idea of democracy. On a scale of 1 to 10, the importance given to living in a democratically governed country averages 8.6. And nearly 90% of French people support the principle of democratic government. Alternative forms of government do have a certain appeal but this is more the consequence of problems with the electoral system and the political representation than of distrust in democracy.

But what then do people believe are the essential characteristics of a democracy? Among the nine proposed options, the French give high priority to political rights and fundamental freedoms, and then to economic and social rights (see the third figure). This ranking echoes the way in which the welfare state was designed in the twentieth century, by building social citizenship on the basis of political citizenship. Social democratic values are therefore fairly firmly established in French people’s minds. This also testifies to French people’s continuing confidence in the health system, education and social security.

Individualization without individualism

Of course, the more economically and culturally wealthy the French are, the more they are inclined to be morally and altruistically liberal, and the more attached to democracy and confident in political institutions they are. But these differences are no more pronounced than in the past

Most of the trends presented are part of a broader trend; the rise of individualization, because the French want to have more of a say in everything. They want the freedom to have the family relationships they want and not be constrained into a normative mold. They want their work to be fulfilling and not just a way to pay the bills. They want to be consulted on local decisions, to defend certain causes, and even to change the way society is organized.

This individualization has been steadily rising over the past forty years. Yet, individualization shouldn’t be confused with individualism or social egoism, which is on the wane. The pessimistic hypotheses about a decline in values and cohesion is therefore far from proven. In fact, the more the French adopt the values of individualization, the less individualistic they tend to be.

Methodology

The 2018 survey was conducted in France by about twenty researchers from several social science laboratories and led by PACTE research lab (Sciences Po Grenoble, CNRS, UGA).

The main random sample comprises 1870 people, residing in France, aged 18 and over, plus an additional sample of 721 young people aged 18-29, selected by quota. The face-to-face interviews were conducted by the Kantar Public survey agency from March to August 2018.

The survey has benefited from numerous partnerships: the TGIR PROGEDO (CNRS-EHESS), the National Institute of Youth and Popular Education (INJEP), the Government Information Service (SIG), France Stratégie, EDF, the National Fund for Family Allowances (CNAF), the International Federation of Catholic Universities (FIUC), Sciences Po Paris (FNSP) and Sciences Po Grenoble (Pacte).

This post is an adaption of a piece originally published in Le Monde (2019/04/25). The complete results are published in a book by Pierre Bréchon, Frédéric Gonthier and Sandrine Astor (eds.): La France des Valeurs. Quarante ans d’évolutions, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, coll. Libres cours Politique, 2019. Website: www.valeurs-france.fr