José Francisco Lynce Zagallo Pavia is Associate Professor at Lusíada Universities of Lisbon and Porto, Visiting Professor at Sciences Po Grenoble (2021)

The aim of the article is to call the attention to the ongoing process of the extension of the platform’s shelves and to the challenges and controversies that this process could generate. There are a few countries that could be beneficiaries of this process, due to their specific geographic situation, and others that have almost nothing to gain. In Europe, some countries have an advantageous geographic situation, like Portugal, Spain, Ireland, France and the United Kingdom; and others do not have that, like Germany, Italy, Poland, Belgium, Greece, Sweden, etc.

Could we, in the near future, witness a situation where the countries with a disadvantaged geographic situation could push this issue to the European Union level? Due to their disadvantage in this process, it could be of their interest to advance to what was called “The European common sea”, thus creating a common European Union Policy on Maritime Issues. How can we harmonize these intentions with national interests, namely from the perspective of a country like Portugal?

This is an ongoing controversy that brings us to the never-ending debate between those who advocate for a deeper integration in the European policies (the Eurocrats) and those who think that we have gone too far, that it’s time to stop and rethink this process (the Eurosceptics, sometimes also Sovereignists)

The extension of the platform shelves

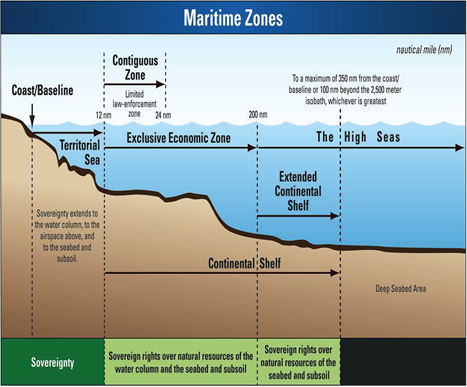

The extension of the platform shelves is an ongoing process that could represent for some coastal States a unique opportunity, not only in economic terms, but also in geopolitical ones. According to the Montego Bay Convention on the Law of the Sea also known as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) is a region that stretches a distance of no more than 200 nautical miles from a nation’s baselines. The figure below provides an overview of the maritime zones:

Source: “Gulf of Guinea Maritime Security and Criminal Justice Primer(accessed 27/06/2017)

Generally, the rules regarding the High Seas, set forth in Articles 88 to 115, apply to the EEZ (Art. 58). Within its EEZ, a nation may explore and exploit the natural resources (both living and inanimate) found both in the water and on the seabed, may utilize the natural resources of the area for the production of energy (including wind and wave/current), may establish artificial islands, conduct marine scientific research, pass laws for the preservation and protection of the marine environment, and regulate fishing (Art. 56; Art. 61-64).

The continental shelf is defined as “a real, naturally-occurring geological formation. It is a gently sloping undersea plain between the above-water portion of a landmass and the deep ocean. The continental shelf extends to what is known as the continental slope, a point at which the land descends further and marks the beginning of the ocean itself. It is host to most of the world’s oceanic plant and animal life and plays a vital role in energy production, from offshore oil and gas reserves to renewable energy resources”.

The maritime States (including those in Europe) have now the opportunity to extend its EEZ rights up to 350 nautical miles; to do so, they have to deposit their claim at the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). This claim is a scientific and legal document where the State presents its rationale, thus requiring a previous study of the seabed, the geophysics, the tectonics and also the legal justification. On top of that, some of those areas have immense economic and scientific potential, thus creating huge expectations.

Those who have filed their claims might be in conflict with those of their neighbors, resulting in maritime borders disputes, as is already the case between Portugal and Spain in the Madeira Archipelago Sea and the Canary Islands. This dispute is a minor one, but it is not yet solved. Spain has a similar bone of contention with Morocco. The International Community, namely the European Union, could play here a positive role by establishing mediation efforts in order to contribute to an insight into the maritime dimension and, thus, toning down the growing tensions between the States.

The Portuguese claim

Portugal is a maritime nation. Since the early days of independence and sovereignty, back to the XII century, that the nation´s destiny is inextricably connected to the sea, by geographic, historic, economic and political reasons. The Portuguese discoveries and expansion were a maritime venture and the Portuguese empire was a seaborne empire.

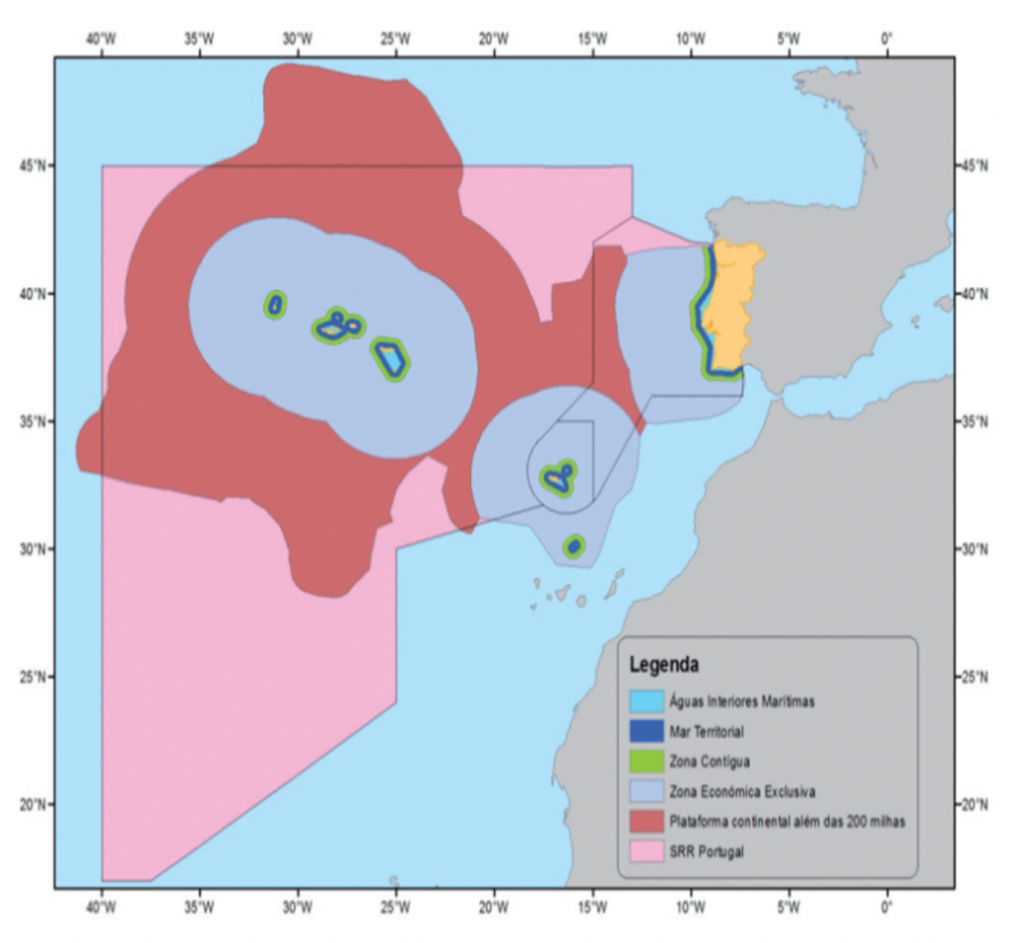

Even today, after the loss of the overseas territories, Portugal is a maritime nation, due to its privileged geographic situation, consisted of a triangle between continental Europe (the western part of Europe) and the Azores and Madeira archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean. This privileged geographic situation constitutes an immense added value for its geopolitical and geo-economics dimensions. The EZZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) under its control is one of the largest in the world and its potential in all domains is far from being exploited.

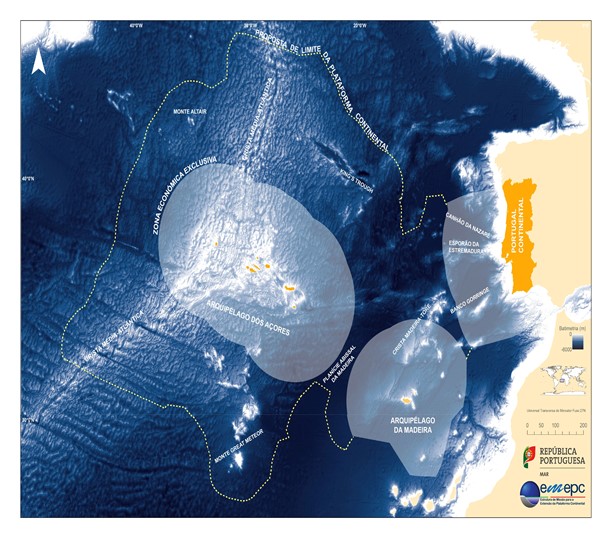

In 2009, the Portuguese government deposited their submission for the extension of its platform shelve. If this submission turns out to be accepted, Portugal will be the country in Europe with the largest area of sea under its jurisdiction – with the exception of the overseas territories of France and the United Kingdom – and one of the largest in the world, as evidenced by the two figures below.

Source: “Zonas Marítimas sob Soberania e/ou Jurisdição Portuguesa” (Accessed 09/07/2018)

Source: “Extensão da Plataforma Continental” (accessed 09/06/2018)

It is key to make sense of the rationale behind the Portuguese claim:

“Portugal signed the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Hereinafter referred to as the Convention) on the day it was opened for signature and ratified it on 14th October 1997. The Convention came into force for Portugal on 3rd December of the same year, 30 days after its deposit with the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The rights of Portugal in respect of the continental shelf that constitutes a natural prolongation of its land territory exist ipso facto and ab initio by virtue of its sovereignty over its land territory, as reflected in article 77 of the Convention. (…) The submission uses all available information and every effort has been made to interpret the data consistently and in accordance with the internationally accepted legal and scientific opinions.”

The results of this submission will be known in a couple of years, but there are already vested interests under way. There are evidences that, particularly in the Azores Sea, some conventional energy resources – like gas and oil – and also unconventional ones – like gas hydrates – are abundant. Furthermore, new research has discovered “marine biotechnology that may contribute to diverse functions, namely the energy through bioenergy production from seaweed, but also the health & well-being function (through production inputs for the pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries), materials & artifacts (through biomaterials), nutrition (inputs for nutraceutical) and environment”. In addition, there is evidence of abundant polymetallic sulphides and cobalt crusts in the Madeira sea. The prospects for research and development purposes, but also for economic ones are notorious, thus the vital importance of this claim.

The Europeanisation of Maritime issues and the debate

The international shipping industry is responsible for the carriage of around 90% of world trade, so the food security, the energy security, the environmental security and the overall economic and military security are unattainable without the security of the sea-lanes. Europe has an historic relationship with the sea, as almost half of the EU population lives less than 50 Km from the sea. Thus, it is not surprising that the EU has successively been advancing in an attempt to communitarize the maritime issues. Several documents in this regard have already been approved, and even an Integrated Maritime Policy has been accorded.

The debate, especially for a country like Portugal, is whether these European developments are beneficiary, or not; now that the country is claiming an immense ocean area that could bring along scientific, economic and geopolitical gains, among others. Some argue with references to the Sovereignty, National Interests, Independency, geopolitics, power politics, Geo-economics, National Strategy, etc, to criticize the advances on the creation of a European common sea, stating that these advances will only beneficiate the stronger and richer States of the EU. The argument is that Portugal – as a maritime nation for centuries – should keep this domain in national “hands” as a way of escaping to a destiny of total irrelevance and exiguity in the EU. The resources and potential gains and benefits of this area would serve – firstly – the Portuguese national interests and not others.

To support this argument the example of the EU common fisheries policy is always used: Portugal is the one of the countries in the world with the higher consumption of fish per capita; it is one of the countries in the world with a larger maritime area under its jurisdiction (the EEZ), but imports more than 50% of its fisheries consumption. The main reason for this situation is – for some – the EU common fisheries policy. These arguments are not new, the debate between Eurosceptics and Euro-enthusiastics now following on with oceans governance.

A competing view argues that Portugal alone has no capacity to take advantage of this immense area. The financial constraints and the lack of resources (naval resources, technological resources and scientific capabilities) pose inescapable difficulties to this endeavour. The EU cooperation, and ultimately, a European common sea, would be a win-win situation, even for the land-locked countries in Europe. There are already good examples of scientific missions, of certain European countries, in Portuguese waters, namely in Azores.

The controversy could derive from the politicization of this subject, turning it into a “political weapon” to criticize the government and/or the EU. Populist movements and far-right or far-left political parties could use the argument of the national Interest, to put pressure on the governments. In past years, the EU common fisheries policy was already used as a political tool in favour of the Brexit. Governments could take actions, not in favour of the general interest or the common good, but pressured by activist movements or the circumstantial public opinion, that could lead to decisions that have no turning point.