This post is also available in:

English

English

In the context of growing globalization, more and more people are mobile internationally, whether it is professionally or in their private lives. Over the last two decades, study abroad programs have been made available to more and more students in higher education, in Europe notably thanks to the Erasmus program. International student mobility has been strongly encouraged by public education policies because of its contribution to human capital in the context of the contemporary global knowledge economy. Overall, international student mobility receives very positive feedback from students, future employers, and public institutions. However, some returning students also mention that they spent most of their time with other students from their home country, talking in their mother tongue.

Study abroad stays have been introduced in many student curricula with the objective to develop the students’ intercultural competence through significant international experience. To succeed in international interaction, that is to say, to understand its interlocutors and to be understood by them, intercultural competence is essential.

Intercultural competence: a key professional competence

Each of us is a bearer of fundamental cultural behaviors, values and assumptions, shared within the group or country of origin. The intercultural encounter is the one that connects people from different cultures, including national cultures. Intercultural competence is the ability to draw on personal resources and traits to understand the specifics of intercultural interaction and to adjust one’s behavior to these specifics.

Intercultural competence is considered as a key competence in companies and international organizations. It is seen as an important criterion for the adaptation of the international manager or foreign assignee, as necessary for successful interactions within multinational companies and international organizations and as one of the key performance factors of intercultural team leaders. Intercultural competence is partly acquired through a learning process that is initiated by intercultural experiences. Extended stays abroad can be the occasion of a more important apprenticeship.

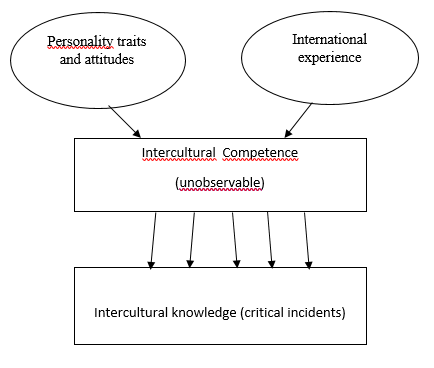

Intercultural competence includes four types of components: attitudes, personality traits, cognitive abilities and knowledge, and behavior. Personality traits and attitudes that are most frequently mentioned in the literature as being strongly linked or equivalent to intercultural competence are open-mindedness, lack of ethnocentrism, emotional stability, empathy, attributional complexity (i.e., the extent to which individuals are inclined to explain behaviors in a complex rather than a simple way), and tolerance for ambiguity. Relevant personality traits are measured through multiple item scales such as in the “multiple personality questionnaire” (MPQ, Van der Zee & Van Oudenhoven, 2001). Our study includes the nine personality traits. The cognitive dimension of intercultural competence, intercultural knowledge, can be measured through the critical incident technique.

Critical incidents are short stories of cross-cultural situations and encounters. They are considered as critical because they are likely to be interpreted differently by people from different cultures, and because they tell of misunderstandings that might result in conflict. Each critical incident is followed by several possible answers that include an interpretation of the situation, potential courses of action, or future events. “Wrong” answers reflect ethnocentric considerations from other cultures or a stereotyped worldview. In our study, intercultural knowledge has been measured through five critical incidents, see Bartel-Radic (2014) and Bartel-Radic and Giannelloni (2017) for more details about this method.

A longitudinal survey among Science Po Grenoble’s bachelor students

To understand under which conditions and in which contexts international student mobility augments intercultural competence, we collected survey data among two student cohorts of Sciences Po Grenoble. All of the students are required to study abroad during the second year of their bachelor’s. To identify the impact of this one-year study stay abroad on their intercultural competence, we ask them to complete two online surveys. Before the international mobility, we collected information on their characteristics and intercultural competence. At the end of their study stay, a second survey was devoted to collecting information about their study stay and to measuring again their intercultural competence. 214 students answered the first-stage survey at the end of their first year of study, 204 responded after the study abroad, representing a response rate of approximately 50%. 114 students have completed the questionnaire before and after their study stay. At the end of their international mobility, the average age of the students was 20, and 68% among them are female.

The model that we will put to the test is presented in Figure 1; it questions the impact of international experience and personality traits on international competence. We consider intercultural competence as an unobservable variable. But the higher a person’s intercultural competence, the better he / she will understand cultural differences and intercultural interaction, which means the better he / she will interpret “critical incidents”.

Impact of international experience and personality traits on intercultural competence: theoretical model

Finally, our results first show that four variables, namely open-mindedness, emotional instability, age and gender, explain 17% of intercultural competence:

- An increase by 20% in open-mindedness increases intercultural competence by 35% whereas an increase of emotional stability by 20% reduces intercultural competence by 17%.

- One of the most robust results of this study is that women systematically achieve higher intercultural competence than men (+23%). It coincides with Rueckert and Naybar (2008) who found women to be more empathetic because of neural differences.

Under which conditions does international student mobility increase their intercultural competence?

The introduction of additional variables, describing international experience in the model, improves the understanding of intercultural competence, as about 25% of intercultural competence is henceforth explained (+ 8%). Our results reveal the positive influence of three additional variables on intercultural competence:

- to have followed courses in English increased intercultural competence by 12%,

- to have experienced negative emotions like disgust (+15%),

- and to have experienced conflicts with students from other countries regarding the objectives and processes of work groups (+8.5%).

Conversely, some interactions during the international mobility have a negative effect on intercultural competence.

- This is the case when students participate in workgroups with other foreign students who do not come from the host country (-10.4%),

- or if they follow courses taught by international professors (-8.5%).

The role of conflict, emotions and complexity in the learning process

Interestingly, negative experiences, like having felt disgust, or having experienced conflict within student workgroups strongly encourage intercultural competence. Both elements somehow give support to the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954) stating that contact between hostile groups might reduce negative stereotypes. The negative impact of emotional stability on intercultural competence might show that “emotional instability” measured in the survey expresses the consequences of these negative emotions and conflicts on the student’s feelings. Conflict is an important engine of change because it is a particular form of interaction including destructuration and re-structuration, making people conscious of something – here, cultural differences.

Moreover, the complexity of the intercultural experience decreases intercultural learning. A confrontation to a higher cultural diversity (courses by international professors and working with foreign students, both not from the host country) has a negative impact on intercultural competence. Conversely, having followed courses in English (and not in the local language, which diminishes complexity) has a positive impact on intercultural competence. Therefore, if cultural diversity encountered during the international mobility is too high, students make less sense of the cultural differences they are confronted with, and display lower intercultural competence.

References

Allport, G. (1954), The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA, Addison-Wesley.

Bartel-Radic, A. (2014). La compétence interculturelle est-elle acquise grâce à l’expérience

internationale? Management International, 18 (Special Issue), 194-211.

Bartel-Radic, A. & Giannelloni, J.-L. (2017). A renewed perspective on the measurement of

cross-cultural competence: An approach through personality traits and cross-cultural

knowledge. European Management Journal, 35 (5), 632-644.

Rueckert, L., Naybar, N. (2008). Gender differences in empathy: The role of the right

hemisphere. Brain and cognition, 67 (2), 162-167.

Van der Zee, K. I. & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2001). The Multicultural Personality

Questionnaire: Reliability and Validity of Self- and Other Ratings of Multicultural

Effectiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 35 (3), 278-288.